Have you ever wondered what options would be available to your company should it get into financial difficulty? Does your company have a ‘plan B’ and how practical and realistic is it? These are questions (re)insurance companies may soon need to answer. Recovery and Resolution Plans (RRPs) have already been introduced in the banking industry. A recovery plan identifies options to restore financial strength when the company comes under severe stress. Resolution refers to the situation when a firm is no longer viable or likely to be no longer viable, and has no reasonable prospect of becoming so. In this blog I outline a few insights the insurance industry can learn from the recovery and resolution planning process which the banking industry has already commenced. (Re)insurance companies may find this useful particularly in light of the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) opinion issued last July recommending a harmonised recovery and resolution framework for all insurers across the EU. This is an area of focus for the CBI, with Ed Sibley reiterating that an appropriate recovery and resolution framework is necessary in his speech delivered to the Insurance Ireland, Annual President’s Conference, in November.

Based on the feedback from the banking industry, it would appear that there is more to recovery and resolution planning than meets the eye. In the banking industry, recovery plans, for example, are intended to be living documents which demonstrate that the recovery strategies presented can be implemented in reality—and that is not an easy task.

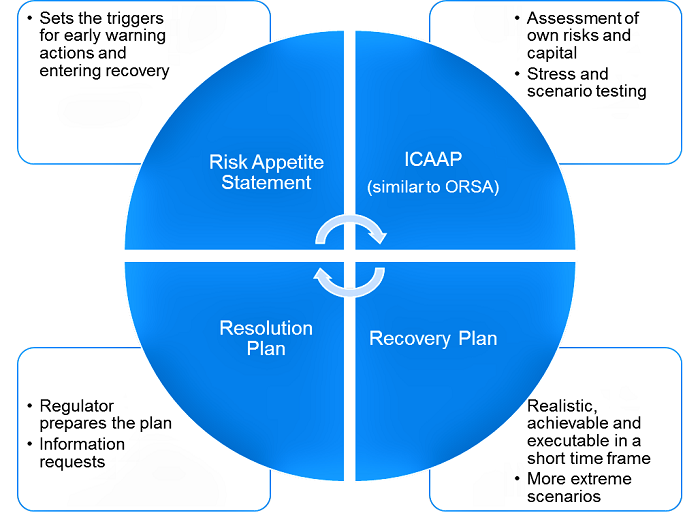

The following diagram illustrates the embeddedness of recovery plans within banks as well as some of the key considerations which I will expand upon in this blog.

Recovery plans can span hundreds of pages as the practicalities of recovery strategies are explored in great detail in order to have a plan of action in place that is realistic, achievable and capable of being put into action straight away. Regulators expect a short timeframe for implementation of a recovery plan, with the recovery strategies presented typically required to be fully executable within a 12-month period. In addition, it is expected that the recovery strategies take account of the particular scenarios the company may find itself in. For example, the recovery strategies may vary depending on whether an idiosyncratic or a systemic risk has materialised, given that the options a company could take when it alone is in financial difficulty compared to when many companies are in the same boat may well be different.

The level of detail required and the operational plans for these options should not be underestimated. For example, practicalities such as setting out the specific counterparties that would be involved in the recovery strategies presented, what mechanisms are in place to set up data rooms and the need to actually line up investment banks could all be required depending on the strategies considered. Of course, proportionality is a factor, with organisations and business activities posing greater threats to the core economy receiving the most focus.

The Financial Stability Board defines resolution as 'when a firm is no longer viable or likely to be no longer viable, and has no reasonable prospect of becoming so.' I find it interesting that while the bank leads the development of its recovery plan, it is the regulator who prepares the resolution plans, and they would typically not be disclosed to the company. The work required for banks, therefore, has been split between the drafting of recovery plans and responding to queries from the regulators to assist with their own development of resolution plans for the companies.

The development of the initial recovery plan undoubtedly requires significant effort from companies. A number of iterations are typically required for these plans. The regulator may request changes or additional items for inclusion, particularly in the initial plan, as both the regulator and the company evolve on what their expectations are for such plans. The information requests from regulators can be numerous and companies require significant resource availability in order to be able to deal with these requests and liaise with regulators on these plans. For example, regulators can require detailed information regarding the legal structure of groups, such as breakdowns of historical profits and losses, including holding entities. This can be challenging, especially when legal structures are complex.

Recovery plans are, of course, not based on random ideas or situations which could arise. They are a natural extension of companies’ financial projections, stress/scenario testing and general risk management. In banking, regulators require that the recovery plan is entirely consistent with the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP), which is similar in concept to the Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA) for (re)insurance companies. Indeed, consistency across the board is expected, including consistency with the company’s risk appetite statement. This, it seems, is a vital element of the recovery planning process.

To add to the ever-increasing sign-off required of boards of directors, recovery plans, too, must be approved by boards, which are expected to have a thorough understanding of the process. Indeed, there is an expectation for the impact of business decisions on the recovery plan to be considered throughout the year, which introduces an expectation of what is almost like the Solvency II requirement that the ORSA play a meaningful role in the business. The idea of the recovery plan as an extension of the ORSA, therefore, feels quite appropriate here.

Going back to the topic of resolution, there is a single resolution authority in Europe for the banking industry, although there is no clear definition of when companies enter resolution as such trigger points are (presumably) contained within the resolution plans. There have been differing views around the rescue last year of two Italian banks (Veneto Banca and Banca Popolare di Vicenza), with some commentators in the financial press believing that the spirit of the relevant European directive, the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD), has not been fully applied. Questions therefore remain as to precisely how any resolution framework for the insurance industry would be applied in practice, and what the thresholds for officially entering resolution, as opposed to normal insolvency, would be.

Of course, the underlying nature of banks and (re)insurance companies is fundamentally different. Nonetheless, the EIOPA opinion issued last month recommends that 'a consistent approach should be followed taking into account the already existing recovery and resolution framework for banks and the potential harmonised framework for insurers.' As you can see from the above paragraphs, there is a lot we can learn from our banking counterparts, who have significant practical experience to guide both insurance companies and regulators in their development of RRPs, even if the specific contents of those plans are not directly relevant to insurers. In the meantime, we in the (re)insurance industry await more formal instruction and are starting preparation for what is likely to come in this space.

Bridget MacDonnell is a consulting actuary with Milliman and a member of the SAI's Enterprise Risk Management Committee.

The views of this article do not necessarily reflect the views of the Society of Actuaries in Ireland, the Enterprise Risk Management Committee, or the author’s employer. The article was edited by the Communications Subgroup of the Enterprise Risk Management Committee.